Osteoporosis is quickly becoming a household word, and authorities now suggest that nearly 45 million Americans are facing a major bone health threat. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation, an estimated 10 million people in the US today have osteoporosis, and an estimated 34 million are at risk of osteoporosis due to low bone density. Further, while we think of osteoporosis as a “woman’s disease,” more than one-quarter of the 45 million of those at risk are men.

Osteoporosis, by its most scientific definition, is a disorder characterized by low bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue associated with bone fragility and an increased vulnerability to low-trauma fractures. Thus, in the scientific sense, osteoporosis is diagnosed only upon occurrence of a low trauma fracture. The hip, spine, wrist, and forearm are common sites of such osteoporotic fractures. Because there are few symptoms associated with bone loss, many are unaware that they are indeed losing bone mass and at risk of osteoporosis.

There are ways to detect low bone density and ongoing bone loss. It is not easy, however, to predict who will actually suffer an osteoporotic fracture. Bone density tests attempt to measure bone mass in various areas of the body, and markers of bone resorption turnover can tell if you are likely breaking down excessive bone at any given time. These tests can detect low bone density and high bone breakdown before a fracture occurs, and thus help identify your chances of a future fracture. They cannot, however, predict who will fracture. For example, over half of all women who experience an osteoporotic fracture do not have an “osteoporotic” bone density. They have either just moderately low bone density, known as osteopenia, or even normal bone density. Given this, everyone, even those with good bone density, would do well to maintain a strong bone-building program.

While there is no way to totally reverse osteoporosis, there are many ways to prevent, halt, and significantly reverse low bone density and low bone strength. Because the average woman has acquired 98% of her skeletal mass by age 20, building strong bones during childhood and the teenage years is the first line of defense. Yet in adulthood, and even in old age, we can regain bone mass and strength. And as we age, it is particularity important to consider prevention, causes, treatment, and possible risk factors of osteoporosis.

Passionate about bone

H ow does one develop a love affair with bone?

ow does one develop a love affair with bone?

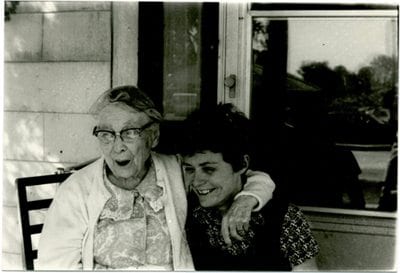

In my case, it began when my alert and active grandmother, who had both osteoporosis and rickets, died at the age of 102 after experiencing a hip fracture. I often wondered just how long she might have lived had she not fractured her hip. Then, at age 36, I was told that I had receding gums. I recognized that this was an early sign of osteoporosis, and I was motivated to learn everything I could about building bone strength. Finally, as an anthropologist I knew of populations in many parts of the world that did not experience osteoporosis as they aged. With this awareness, I became determined to uncover why nearly half of US Caucasian women age 50 and over would suffer one or another needless osteoporotic fracture their remaining lifetime.

These personal experiences ignited my interest in bone health and propelled me to undertake a comprehensive “rethinking” of osteoporosis, sorting fact from fiction. To this end, I founded the Better Bones Foundation (formerly the Osteoporosis Education Project, or OEP) — a nonprofit, public interest group dedicated to exploring the full human potential for building, maintaining, and regaining bone health.

At Better Bones, we have been rethinking the true nature, causes, and best prevention and treatment of osteoporosis for more than two decades. We now know that osteoporosis is a rather complicated disorder, but often presented as a simple problem of calcium or estrogen deficiency. As an anthropologist, I have been able to rethink osteoporosis from a cross-cultural perspective, developing critical new insights into this potentially crippling bone disorder.

In rethinking osteoporosis, we have found the nature of osteoporosis to be different than that commonly held. For example, hip fracture rates vary 30-fold around the world, with some cultures being almost immune to osteoporotic fractures. Cultures with the highest calcium intake have the highest osteoporosis rates. Further, in many countries, such as Germany and China, people have lower bone density than we do, yet they fracture much less than we do in the US.

Rethinking the causes of osteoporosis

Adequate levels of many minerals like calcium, magnesium, manganese, zinc, and boron are important to bone. Vitamins are also essential. Vitamin D, well known for its role in calcium absorption, is taking on new importance as we learn more about its vast physiological functions, while simultaneously finding that a growing number of us are actually vitamin D-deficient. Vitamin K, especially in the form of vitamin K2 (MK-7), is another key bone-building nutrient you will be hearing more about. We are coming to realize that vitamin K is not only the “glue” that binds calcium to bone, but also the key factor in preventing calcium from hardening the arteries. Vitamin A, on the other hand, should probably be limited to less than 5000 IU daily, as high doses of vitamin A (but not beta-carotene) might hamper bone health.

We’ve also learned how many other dietary and lifestyle factors can affect our bones. For example:

- Excessive intake of coffee, sugar, fat, alcohol, and protein also damage bone. Yet many who take one or two alcoholic drinks a day actually have better bones than nondrinkers, and low protein intake is just as bad for bone as excessively high protein intake.

- Exercise builds muscle and strength builds bone, while disuse causes atrophy of both.

- Rapid weight loss as well as obesity causes bone loss, so dieters need special nutrient supplement programs.

- Strong medications like corticosteroids have been long known to damage bone. Now research shows that other common medications, including some antidepressants and acid blockers, also damage bone and increase one’s risk of fracture.

- Dear to my heart, the most hidden cause of osteoporosis, namely chronic low-grade metabolic acidosis, is finally becoming recognized as a major “bad guy” for bone health.

Rethinking the best prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

Recognizing the complexity of osteoporosis, we at the Better Bones Foundation have developed a comprehensive program for bone health maximization. Each of the steps is life-supporting in itself, making this program one that builds better bones and better bodies.

Better Bones, Better Body® is a great motto for all of us. It is never too early or too late to build and rebuild bone naturally! Furthermore, everything we do for bone can be, and should be, good for the rest of our body as well!